Coral Spawning Work goes Ahead

For the past three years, members of the Restoration & Remediation Working Group (RRWG) in Bolinao have been carrying out experiments to see if corals reared from larvae can be used effectively for the restoration of degraded reefs.

A series of larval rearing experiments were planned at Bolinao Marine Laboratory (BML) during May 2009. Two days before the full moon, however, the typhoon made landfall at Bolinao.

Despite the typhoon damage, RRWG member James Guest reports that the marine laboratory at Bolinao achieved a successful spawning.

"When I arrived in Bolinao four days after the storm to assist with coordinating the spawning work, I was not sure whether we would be able to do the planned work," says James.

"However, in the days after the storm, staff members at BML had worked hard to get the seawater flowing, aeration running and the roof repaired in the hatchery. Everyone was keen to continue as planned, so the next day we collected 22 gravid colonies of two faviid species.

"Only seven of these colonies were removed from the reef as the remaining 15 colonies were from a 'brood stock' of colonies that were collected and spawned the previous year. This is positive news as it shows that spawned colonies can be kept at protected nursery sites and used again the following year, thus minimising damage to natural reefs."

James says the colonies were transferred to the hatchery and, on the night after collection, researchers noticed colourful egg bundles appearing at the surface of some of the colonies.

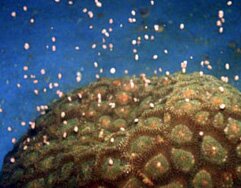

"We began preparations to collect the gametes. As the evening progressed, more of the colonies started to spawn (Photo 1). By the end of the night, all of the 22 colonies had spawned and we had fertilised more than 1.6 million coral eggs. This was the most successful spawning event yet!

"Over the next few days the embryos developed into swimming larvae and had started to settle on small pre-prepared settlement substrates (Photo 2). We hope significant numbers of these corals will grow to a size where they can be transplanted to areas of degraded reef."

James says work from last year shows that early mortality of settled corals is very high; however enough individuals do survive for use in transplant experiments. Although the initial results from this work are promising, much still needs to be done to establish whether corals reared from larvae can be used effectively to restore degraded areas of reef.

"When I left the larvae looked healthy and were settling on pre-designed 'plug-ins' in the hatchery tanks. Everybody from the RRWG pitched in on the main spawning night and this contributed to our success."

Colony of Favites Halicora spawns at the hatchery facility at Bolinao Marine Laboratory on May 14, 2009 (Photo: K. Vicentuan)

|

Montastrea colemani spat (Photo: J. Guest)

|

Long-term efficacy and cost-effectiveness of restoration interventions

The effectiveness of restoration interventions should be judged in terms of what these interventions achieve in comparison to what occurs in natural recovery over at least a five to 10 year timescale.

The Restoration and Remediation Working Group is using standardized artificial structures of sufficient scale and replication to allow long-term statistically rigorous comparisons between outcomes of natural processes and a range of interventions.

Two Working Group projects assessing the cost-effectiveness of restoration interventions over the longer term (5-10 years) are now gathering data in Bolinao, Palau and Mexico. Initial results are expected by the end of 2008.

Enhancing recovery by culture and transplantation of corals

The Working Group is investigating asexual propagation of corals to assist restoration. The challenge of restoration using transplants is balancing the costs of nursery rearing and effective use of limited source material against the likelihood of transplants’ survival.

The effect of the size and structure of coral fragments on subsequent growth and survival for a range of species is being examined. Low-cost approaches involving direct transplantation are being compared to more expensive approaches involving periods of in situ culture prior to transplantation to damaged reefs.

Interesting results are emerging on the effect of transplantation on colony fecundity and the effect of fragmentation on fecundity of donor colonies. Data on competency curves continue to be collected for a range of species in Palau and Bolinao and “coral plug-ins” (wall-plugs with 2 cm diameter concrete heads) are being trialled as settlement substrates to provide a cost-effective method of rearing coral larvae from spat. These trials are at an early stage. Larval enhancement of seven pallet balls was carried out at Palau at the April 2008 mass-spawning.

In Palau, a disease outbreak in some of the mid-water culture cages in January 2008 resulted in disappointing survival of Acropora being co-cultured with snails, while transplanted juveniles suffered from fish grazing. However, similar work being conducted at Akajima, Japan shows 10-50 times better survival.

Enhancing larval recruitment

The Working Group is looking at the sexual propagation of corals from the larval stage following spawning. This involves a higher level of technology and much higher implementation costs but does offer the potential of rearing hundreds of thousands of sexual recruits for restoration.

Research is being carried out in Palau International Coral Reef Centre with additional work on coral reproduction at the Bolinao Marine Laboratory in the Philippines.

Despite a Crown-of-thorns outbreak and Drupella attacks as well as the bleaching in 2007, experiments continue. Data on the relative robustness of different species is increasing. Methods for more cost-effective culture and deployment of corals are being refined. Overall, it is becoming apparent that any restoration project without considerable maintenance and monitoring (and adaptive management) is more than likely doomed, and the risks to transplants need to be fully realized, and where possible reduced, by judicious selection of species.

Pegs post promise in restoration

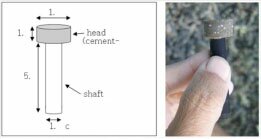

Fig. 1. Coral peg . Polyps (10+) settled on the side of the head of a peg.

Fig. 2. Coral colonies on top of a peg. |

The potential of a "coral peg" for assisting reef restoration using sexually-reared corals has been demonstrated, based on results from a pilot experiment in Japan. Adopting an approach suggested at a CRTR Restoration and Remediation Working Group workshop, Japanese researchers started pilot-testing 200 pegs during June 2007.

In November 2008, 17 months after settlement, corals on 76 out of 100 pegs survived (Fig. 2b). Survival rates of corals on a sample of 20 pegs were 0–35% (mean = 6.4%). Some colonies fused with each other and were counted as one. Colonies tended to grow from the side of the head and grew up to 66mm in diameter and 41mm in height. The smallest was 9mm in diameter and 6mm in height.

The researchers,

Prof. Makoto Omori and

Dr K. Iwao, based at the Akajima Marine Science Laboratory (AMSL), Okinawa, where the pegs were developed, intend to maintain the cultured corals in cages before transplanting them to bommies at Akajima.

The coral peg is 60mm in total height; the head (cement mixed with quartz sand) is 18mm in diameter and 10mm in height, and the shaft (plastic) is 10mm in diameter and 50mm in height (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2a.

17-months-old coral on top of a peg |

The experiment began at a time when the researchers were producing planula larvae of Acropora tenuis in the laboratory. Beforehand, the pegs were placed in seawater for one month for preconditioning of the surface. These pegs were immersed in a water tank (80L) containing 10,000 individuals of 6 day-old planula larvae for 2 days (10,000 individuals for the first day and another 10,000 individuals were added next day; that is 20,000 individuals in total). An average of 62.5 larvae settled and metamorphosed on the peg (N=40). They were then cultured with juvenile top-shell snails (to reduce algal growth) in a cage at 1.5-3.0 m depth in AMSL's mid-water nursery (Fig. 2). At a CRTR workshop on reef restoration in August 2006, there was a suggestion that combination of the nursery techniques being used for asexual propagation of corals (Shafir et al. 2006) and those for sexual propagation on tiles (Omori et al. 2008) might provide a better way of getting sexually propagated corals onto the reef. Could juvenile corals be reared either on a plastic pin or wall-plug with a concrete head in nurseries like those developed by Shafir et al. (2006)? According to Makoto, these substrates (pin or wall-plug) can be easily transported and stuck directly into the reef after either drilling or using a hand-auger.

For further information please contact Prof. Omori at

[email protected]